The Nirvik Bureau, Bhubaneswar, 19 December 2025

When the Prime Minister Went Abroad and Nobody Bothered to Watch

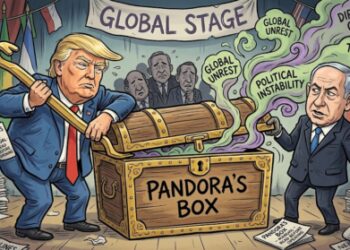

In a nation where even a minister’s cough can trend on social media, the Prime Minister of India went on an ambitious foreign tour and, astonishingly, the country shrugged. No hashtags, no nightly screaming matches, no breaking news countdown to “PM’s wheels touch tarmac.” Just a quiet, dignified silence—if you ignore the syndicated agencies dutifully filing the same three paragraphs across 19 outlets.

This time the PM’s passport stamps read like a connoisseur’s collection: Ethiopia, Oman, and a handful of ceremonies that looked suspiciously like a cross between convocation day and the Filmfare Awards. The tour had all the ingredients—red carpets, foreign medals, solemn photo-ops, and motorcades—yet somehow it played in India like a rerun at 3 a.m.

The highlight, we are told, was the conferring of some of the highest national honours from friendly nations. If diplomacy were a reality show, this would be the “Award Function” episode. There stood the PM, receiving medals and decorations with the same practiced smile that says, “I am deeply honoured, also does this come with free bilateral trade concessions?” At this point, our leader has so many foreign honours he could open a small museum or at least a “National Award Mart” with festive discounts.

But this tour was not just about medals; it was also about the new-age subtle weapon of statecraft: car diplomacy. Once upon a time, global power was measured by nuclear capability; now it is measured by which head of state gets chauffeured in which imported, armored, eco-friendly, plane-proof, missile-averse luxury vehicle. The sight of leaders stepping out of gleaming cars has become the new handshake photograph: if the chrome doesn’t shine, the bilateral ties clearly don’t either.

Car diplomacy works like this:

You arrive in their car to show their respect.

They arrive in your car to show your prestige.

You both sit in a third car to show strategic autonomy.

Somewhere between Addis Ababa and Muscat, the choreography of doors opening in slow motion and flags fluttering on bonnets replaced any need for actual public communication. Who needs a press conference when you have a convoy?

Back home, however, nobody had time to notice the Prime Minister’s automotive ascension or his fresh set of medals. Parliament was engaged in its favourite national sport: not functioning. The Luthra brothers were being arrested, providing the perfect spice-mix of business, scandal, and speculation for prime time. Across the border, disturbances in Bangladesh added just enough regional instability to keep everyone busy looking worried on camera.

Result: the foreign tour slid neatly under the radar, covered faithfully by a small pool of syndicated agencies who believe in recycling—recycling adjectives, that is. “Historic,” “path-breaking,” “far-reaching,” and “landmark” were deployed with such efficiency that one could not tell if they were about a trade agreement, a courtesy call, or the inauguration of a parking lot.

For once, the PM’s trip abroad did not dominate the discourse. No “Where is the Prime Minister?” debates, no “Should he travel at a time like this?” think pieces. The Opposition was too busy inside the House, the anchors were too busy outside their studios, and the citizenry was too busy inside their EMIs.

Now that the tour is over, the medals unpacked, and the cars parked, the question is: what next?

Will we see a special address to the nation explaining how one more international award has finally solved poverty, unemployment, and price rise? Will there be a fresh slogan, perhaps “Videsh Mein Vandan, Desh Mein Chintan”? Or will the communication strategy remain elegantly simple: show the photos, skip the questions, and let the syndicated adjectives do the heavy lifting?

Maybe the real diplomatic masterstroke was exactly this: conduct a full-fledged international tour so routine, so predictable, so perfectly stage-managed that the country didn’t even feel the need to react. The Prime Minister left, the Prime Minister returned, the crises continued, and car diplomacy rolled on—smooth, polished, and slightly out of reach.

After all, in the grand theatre of democracy, someone has to play the global statesman, even if the audience is too distracted to clap.