The Nirvik Bureau, Bhubaneswar, 18 February 2026

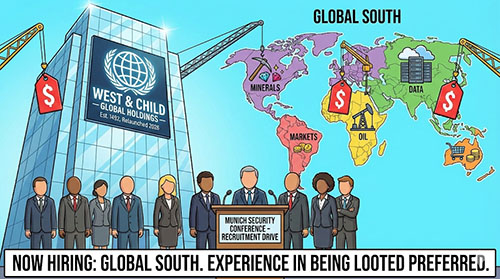

When Marco Rubio stood up in Munich and lovingly described the last five centuries of Western expansion as if it were a motivational TED Talk for colonisers, one could almost hear a creaky wooden signboard being repainted in the background: “East India Company Pvt Ltd” carefully upgraded to “West & Child Global Holdings (Inc.) – Recolonising, but Make it 21st Century.”

This time there are no redcoats, only red ties. No gunboats, just “Western supply chains for critical minerals not vulnerable to extortion from other powers” — a poetic way of saying, “Your lithium is our birthright, kindly sign here.” The Global South, we are told, is not a partner but a “market share” to be captured in the glorious project of a “new Western century.” Apparently the old Western centuries of slavery, plantations, and famine weren’t quite new enough.

Rubio helpfully reminded the audience that decolonisation was basically the West’s “retreat”, rudely accelerated by “anti-colonial uprisings” and “godless communist revolutions” that had the bad manners to object to being ruled from several thousand kilometres away. Anti-colonial struggles, in this telling, were not freedom movements; they were revenue disruptions in an otherwise healthy portfolio.

Enter Act II: Trump & Sons, Global Empire Division. With Venezuela’s president kidnapped and its oil trade brought under Washington’s “informal management”, the company has clearly moved from trading spices to trading sovereign nations, now with better branding and worse PowerPoint. India is politely sanctioned for buying Russian crude, then nudged to buy Venezuelan oil “under a Washington-controlled framework” – like being scolded for eating at the wrong dhaba and then herded into the franchise outlet next door.

The original East India Company had one small London office “five windows wide” and an “unstable sociopath” named Clive managing things in the field. The updated version has several think tanks, a crypto council stacked with family members, and an “informal Board of Peace” to decide which country gets liberated into compliant supply chains next. Progress is real: earlier we had opium and cotton; now we have critical minerals, AI, digital infrastructure, and, of course, your domestic policy.

Rubio insists “we are part of one civilisation, the Western civilisation,” and that this West must stop putting the “so-called global order” above its own “vital interests”. Translation: Rules-based order is excellent, as long as we write the rules, own the pens, and bill you for the stationery. The Global South’s role is simple: supply the minerals, host the data centres, buy the products, and clap appreciatively whenever a Western leader remembers your country’s name without confusing it with your neighbour.

Analysts have politely called the speech “colonial in tone” and “one of the most explicitly pro-colonialist speeches” of this century. That’s polite-speak for: if this was any more honest, it would come with a tricorn hat and a charter from the Crown. When Rubio talks of “competing for market share in the economies of the Global South,” it sounds less like diplomacy and more like a tender notice for recolonisation, with better legal documentation.

And what of India, the self-declared vishwa guru and proud birthplace of anti-colonial struggle? Experts say that as “beacon of anti-colonialism”, India should condemn Rubio’s project “with the contempt it deserves.” Instead, New Delhi will likely do what any wise postcolonial state does in such situations: express “deep concern”, reaffirm “strategic autonomy”, quietly renegotiate oil discounts, and hope the new East India Company at least remembers to build some railways this time – preferably standard gauge, and with royalty on freight.

After all, history teaches us a simple lesson: colonialism often starts with a smile, a trade agreement, and a very reasonable clause about who owns your future. The difference now is cosmetic: fewer cannonballs, more contracts; fewer viceroys, more venture capital; fewer flags, more logos. The intent, as Rubio so helpfully clarified, remains beautifully consistent — “take back control”, “regain ground”, “prosper in the areas that will define the 21st century.”

Some will say this is merely “strategic competition”. Of course. The East India Company also called itself a trading firm. The rest of us just called it what it was – until it left.