Ambika Prasad Kanungo, Bhubaneswar, 9 February 2026

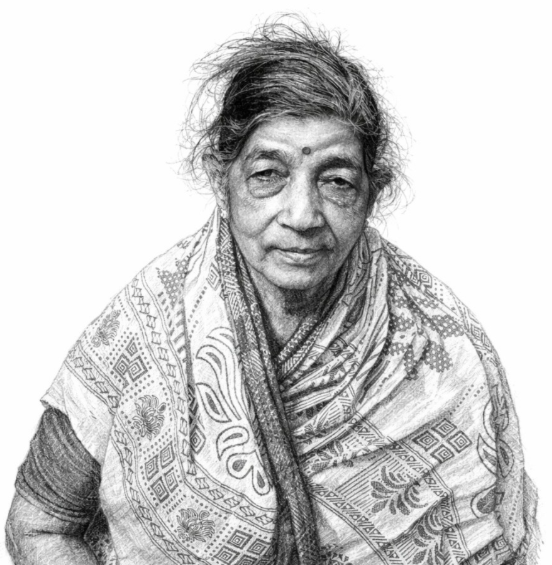

If one were to wander through an old Odia neighbour hood—those sun-soaked lanes that resemble the quieter streets of Malgudi—one would inevitably encounter a certain kind of women. She is not one to command notice; she moves softly through her home, as unobtrusive as a beam of light slipping in through a half-open window. Yet the entire household runs to her rhythm, though no one ever speaks of it, and she herself might be the last person to acknowledge it.

Such women have a peculiar arithmetic, they measure their well-being by how comfortable everyone else is. A frayed curtain troubles them more than a fever, and an unboiled cup of milk can weigh heavier on their minds than their own unspoken aches. They ask for little, expect almost nothing, but give in ways no ledger or census could ever record.

One such woman is Mrs. Kiranabala Nanda, wife of veteran journalist Sri Sarada Prasanna Nanda, Resident Editor of The Pioneer, Bhubaneswar. For years she was simply “Mrs. Nanda”—the gentle, ever-present figure who would appear with a warm smile and vanish before one had found the words to thank her. It struck me recently that although she had served tea to half the press fraternity for decades, very few knew her full name.

I met her on a Thursday evening, at Sarada Babu’s modest yet lively residence office. The place reminded me a little of the old “Malgudi Gazette”—papers stacked like restless pigeons, clerks engaged in earnest debate over headlines, and an editor convinced that the world could be kept in order with discipline, patience, and a typewriter’s descendant. Though in his eighties, Sarada Babu sat upright, absorbed in his screen, spectacles flashing like twin signals of intent.

We had only begun our usual conversation—politics, unexpected weather, and why reporters appear precisely when one is least prepared—when Mrs. Nanda entered with two cups of tea. She carried them as though she were bearing some quiet ritual. She placed them before us and smiled, assuring us without words that everything was just as it should be.

One sip was enough. It was the unmistakable taste of tea brewed by someone who remembers your sugar preference even when you have forgotten it yourself.

When our discussion came to an end, we placed the empty cups on the dining table. Finding her alone for a moment, I asked her a few simple questions—about her life, her marriage. She answered with the straightforwardness of someone who neither exaggerates nor hides anything.

She had married in 1971, she said, with the calmness of a person stating the year of a benevolent monsoon. For about fifty-five years now, she has tended to her husband with the care one usually reserves for heirlooms.

At seventy-three, her routine remains unchanged: she wakes early, prepares his meals, arranges the house, and ensures that everything is just where it should be. She speaks nothing of devotion, but one finds it expressed in warm food, neatly folded clothes, and a silence that has never known complaint.

Meanwhile, her husband continues his journalistic calling with unbroken enthusiasm. Once he leaves for the office, she is left alone with the ticking clock, the kitchen’s familiar noises, and the occasional visitor. Yet solitude sits comfortably with her, like a well-trained guest who knows not to intrude. From their early years in Cuttack, it seems Sarada Babu was never required to buy vegetables. Should someone ask him the price of tomatoes, he might answer with the unaffected confidence of a man who has never paused before a vegetable stall. Mrs. Nanda took over those duties as naturally as others take to morning walks.

Not once in half a century has she complained? She has never raised her voice, blamed her husband, or allowed bitterness to disturb her home. Her life is a quiet reminder that love, to some people, is not a proclamation but a daily practice.

Women like her are the smooth wheels on which the machinery of life turns. Without them the world would still move, but with a little more friction, a little less grace.

In her, one finds the distilled essence of the Odia wife:

Love, spoken through service.

Devotion, whispered through silence.

Strength, revealed through small, unseen sacrifices.

She is the unrecorded poetry of her home—not bound in books, but rising from the clink of a teacup, the fragrance of a timely meal, and the unbroken thread of care that stretches across a lifetime.

The Quiet Loneliness of Modern Homes

In many educated families today, a new kind of silence has crept in—soft, persistent, unwelcome. The children, now settled in distant lands with families of their own, send money home with admirable punctuality. But the affection behind those remittances has thinned, like the fading ink of an old aerogramme.

The once-lively homes of these parents now echo only with the scrape of chairs, the clatter of utensils, and the slow ticking of clocks. The father drifts toward friends—not from enthusiasm, but because the empty rooms at home expand threateningly each evening. The mother moves through her routines without complaint, though every corner of the house still remembers a child who no longer lives there.

Meals are taken quietly, sometimes without a single shared word. Time, once a lively stream, now lies still, as if tired. Their days are anchored only by small rituals—the ringing temple bell, the vegetable vendor’s cry, the occasional phone call from their children.

It is a gentle sorrow, where nothing dramatic happens, yet everything has changed. Parents who once shaped futures now move about like careful guests in their own homes, hesitant to disturb the stillness. They are not abandoned, yet not truly accompanied either. Tradition has not broken; it has only worn thin from the long, steady friction of distance. And the parents who once carried the weight of an entire household, now carry only the faint echo of footsteps that have wandered far away.

In the fading years of life, old parents seldom ask for anything extraordinary. Their desires are modest, almost childlike. A warm voice in the next room. The aroma of a family meal drifting through the house. The sudden laughter of grandchildren spilling into the courtyard. These are the small miracles that keep their hearts steady. Money, though necessary, sits cold and silent on the table. It cannot hold their hand on a lonely afternoon.

What they truly yearn for is the nearness of their own people—especially the daughter-in-law who has, over time, become the quiet bridge between generations, and the grandchildren whose presence lights up corners of the house that would otherwise remain dim. When ageing parents live alone, without the presence of their family, time becomes harder to bear. The days feel longer, the silence deeper. Each time they see their neighbour’s home fill with life—sons returning, daughters-in-law organising the household, grandchildren running happily into waiting arms—a quiet pain settles in their hearts.

Those simple scenes remind them of their own children, now far away. Memories return gently: the warmth of shared meals, the chatter of young voices, the joy of watching their children grow. These memories comfort them, yet they also remind them of what is missing. At times, in the stillness of their solitude, a troubling doubt surfaces: Did we do the right thing by sending our children away to study and build their futures? It is a question born not from regret, but from longing.

And then another fear whispers in their hearts: How long will we live? Will we see our children as often as we hope? After we are gone, is there any way to meet them again?

These thoughts stay with them—soft, unspoken, yet deeply felt.